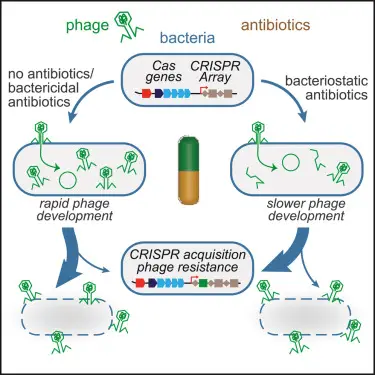

Antibiotics are drugs that help fight bacterial infections. Recently, scientists have discovered that these drugs can also affect the way that viruses, called bacteriophages or “phages,” interact with bacteria. Bacteriophages, also known as phages, are viruses that infect bacteria. They are extremely common in nature and are estimated to lyse (break open) 20–40% of bacterial biomass daily. Bacteria have developed a wide range of defense mechanisms to resist phage invasion, one of which is the CRISPR-Cas system. This system acquires genetic components (spacers) from previous phage invaders and uses them to target and cleave invading phages.

Phages have also developed counter-defense mechanisms to evade the CRISPR-Cas system. One such mechanism is the production of anti-CRISPR proteins (Acr), which prevent the CRISPR-Cas system from attaching to or cleaving the phage genome. However, the Acr synthesis is not always quick enough to completely disable the surveillance system, and the phage may still be cleaved. But, even if the genetic material of the phage is cleaved, the Acr protein will still leave the bacteria in an immunosuppressed state, making it more susceptible to infection by the phage.

The effect of antibiotics

Recent research has demonstrated that the development of CRISPR-Cas immunity after infection with phages that lack Acr activity is favored by the presence of bacteriostatic antibiotics (antibiotics that restrict cell growth without killing). Bacteriostatic antibiotics in sub-inhibitory doses restrict both bacterial growth and phage replication, extending the phage replication cycle and giving bacteria more time to develop new spacers to fight the phage before being lysed. Phage-antibiotic interactions can be either antagonistic or synergistic.

While a mechanistic explanation for the observed interaction is frequently lacking, several different mechanisms have been identified, including antagonistic effects due to a reduction in host RNA synthesis and synergistic effects due to phage-mediated inhibition of antibiotic resistance development in conjunction with antibiotic-mediated inhibition of phage resistance apparition.

Antibiotics target various molecular targets to stop bacterial growth or destroy cells. One of the most popular targets is the ribosome, an enzyme complex that is necessary for translating messenger RNA into functional polypeptides. Antibiotics from a wide range of classes bind to the ribosome, which interferes with the initiation, elongation, or termination of translation. This can occur even at sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations.

In summary, bacteriophages and bacteria have developed a constant arms race to outsmart each other, with bacteriophages evolving mechanisms to evade bacterial defenses and vice versa. Antibiotics can have both positive and negative effects on this interaction, and further research is needed to fully understand the underlying mechanisms.

Reference

Pons, B. J., Dimitriu, T., Westra, E. R., & van Houte, S. (2023). Antibiotics that affect translation can antagonize phage infectivity by interfering with the deployment of counter-defenses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(4), e2216084120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216084120

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.