According to a recent article by The Guardian, one of the UK’s leading scientists, Prof Martha Clokie, has highlighted the need to rapidly scale up the use of experimental therapies based on bacteria-killing viruses, known as phages, in the National Health Service (NHS) to combat the growing threat of antibiotic resistance. Clokie, who has been at the forefront of phage research at the University of Leicester, believes that the approach has been helping an increasing number of patients in compassionate use cases, and could become a routine treatment in the future for chronic conditions such as UTIs and diabetic foot ulcers.

According to Professor Martha Clokie, a leading UK scientist, the NHS must rapidly expand the use of experimental therapies based on bacteriophages (phages) to combat the growing threat of antibiotic resistance. Clokie, who has conducted pioneering research on phages at the University of Leicester, has been involved in a growing number of compassionate use cases where phages have been used to treat conditions such as chronic UTIs and diabetic foot ulcers. She believes that phage therapies could become a routine treatment in the future.

Clokie is due to become the director of the UK’s first phage library, which is set to open in Leicester next month. The library will fast-track the use of phages in the NHS and pave the way for large clinical trials that are required for phages to become licensed treatments. Clokie is concerned about the worsening threat of antibiotic resistance, and she finds it “really shocking”. She believes that without clinical trials, phages will not become mainstream as a medicine, which is the aim.

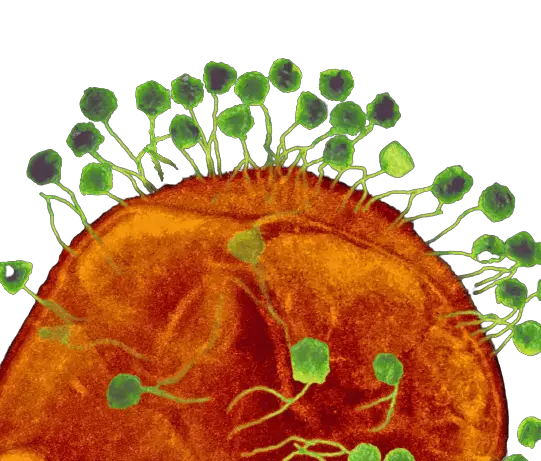

Phages work by infecting bacterial cells and killing them, but they are highly specific in the infections they can target. They have been used successfully in growing numbers of one-off cases, including a teenager in the UK who was dying from a lung infection that was treated at Great Ormond Street Hospital in 2019. However, these one-off cases typically involve scientists spending months in the lab designing expensive, bespoke treatments.

Clokie’s lab is preparing a phage cocktail for a London-based patient with a chronic UTI who is allergic to antibiotics and does not have other treatment options. The lab has a collection of about 2,000 phages stored in a freezer at -80C, and they hope to increase this by about 1,000 samples each year. Phages are found ubiquitously in nature, and phage-hunting involves tracking down those that efficiently kill infection-causing strains.

Clokie’s students have been sent out to dredge muddy estuaries and piles of horse muck in the quest for new species. A set of phages extracted from slime in a stream in Bradgate Park, Leicester, were found to be particularly good at targeting biofilms, which are often seen in chronic bladder infections and are among those under consideration for treating the London-based patient. Clokie believes that despite a growing awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance over the past decade, the outlook has not improved, and doctors are reporting an expanding list of infections showing multi-drug resistance, including E. coli, pneumonia, gonorrhea, and the stomach bug shigella.

Clokie is calling for an update to regulations created with conventional drugs in mind to make it easier to carry out trials that could pave the way for wider use of phages. She believes that cocktails could be designed to treat common infections rather than specific strains in individual patients. The growing use of phages in agriculture as an alternative to chlorine spray in potato production shows that costs are not prohibitive, she said. “They’re not going to replace antibiotics, but they can be used to protect and preserve our antibiotics,” she said. “We can use them in chronic settings, and we can use them in combination with antibiotics. I see it being a really useful complementary treatment.”

For more news visit The phage news page (All phage related news)